Mao Zedong

Founder of the People’s Republic of China and Architect of Chinese Communism

Born on December 26, 1893

Died on September 9, 1976

Age at death: 83

Profession: Revolutionary Leader, Politician

Place of Birth: Hunan Province, China

Place of Death:

Early Life and Political Awakening

Mao Zedong was born on December 26, 1893, in Hunan Province, China, into a relatively wealthy landowning peasant family. Leaving his rural village to pursue teacher training, he was exposed early to the tensions between traditional Confucian society and the rapidly changing political landscape of late imperial China. At the age of eighteen, he joined the Hunan provincial army during the 1911 Revolution, which led to the collapse of the Qing dynasty and was ideologically inspired by the republican movement of Sun Yat-sen.

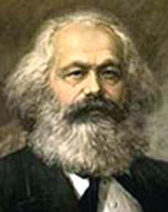

After returning to his studies, Mao graduated in 1918 and worked as a teacher. His intellectual transformation accelerated when he became a library assistant at Peking University. There, he came under the influence of leading Chinese Marxist thinkers such as Chen Duxiu and Li Dazhao. Through their guidance, Mao engaged deeply with the writings of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, joining Marxist study circles that laid the ideological groundwork for Chinese communism.

During this formative period, Mao developed a distinctive belief that China’s vast peasantry—rather than an urban industrial proletariat—would serve as the primary revolutionary force, a concept that would later define Maoism.

Founding of the Chinese Communist Party

In 1921, Mao Zedong attended the First National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party as a delegate from Hunan. He was one of the party’s twelve founding members. The CCP emerged during a period of widespread rural unrest, positioning itself as a revolutionary alternative to the nationalist government led by Chiang Kai-shek.

Initially, the CCP cooperated with the Nationalist Party in a united front. However, ideological divisions soon escalated into open conflict, reflecting global tensions between socialist and nationalist movements following the Russian Revolution led by Vladimir Lenin.

The Long March and the Rise to Supreme Leadership

Between 1924 and 1927, communist-led uprisings were violently suppressed by Nationalist forces. Mao responded by advocating the strategy of “encircling the cities from the countryside.” Under sustained military pressure, communist forces were forced into retreat, initiating the historic Long March from September 1934 to October 1935.

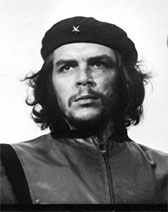

The Long March proved decisive in consolidating Mao’s authority. His leadership during this grueling campaign elevated him to the top of the party hierarchy and established his reputation as a revolutionary strategist, later compared to figures such as Ho Chi Minh and Che Guevara.

Rural Revolution, the Red Army, and Land Reform

Following the Long March, Mao Zedong consolidated power in communist-controlled rural regions, particularly in southern China. He implemented radical land reforms, redistributing land from wealthy landlords to poor peasants, fundamentally reshaping rural society and securing mass support.

To defend these revolutionary zones, Mao organized the Chinese Red Army and established Soviet-style local administrations. In November 1931, with the proclamation of the Chinese Soviet Republic in Jiangxi, Mao was appointed chairman, effectively leading a parallel state within China.

War with Japan and Revolutionary Consolidation

In 1937, Japan launched a full-scale invasion of China, exploiting internal political divisions. While Mao’s communist forces and Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists formed a temporary united front against Japan, deep ideological rivalry persisted throughout the war.

The conflict continued until Japan’s surrender in 1945. During this period, Mao expanded communist influence through guerrilla warfare, political mobilization, and disciplined organization, positioning the CCP for victory in the renewed civil war.

Establishment of the People’s Republic of China

In 1949, Mao Zedong proclaimed the founding of the People’s Republic of China in Beijing. He assumed both state leadership and party control. Defeated Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek retreated with his government to Taiwan, creating a lasting geopolitical division that remains unresolved.

Internationally, Mao aligned China with the socialist bloc led by Joseph Stalin and the Soviet Union. Over time, ideological differences between Maoism and Soviet communism deepened, eventually leading to the Sino-Soviet split.

Economic Campaigns and the Great Leap Forward

Until the mid-1950s, Mao Zedong largely followed Soviet economic planning models. In 1958, he launched the Great Leap Forward, an ambitious campaign that reorganized hundreds of millions of people into more than 26,000 “people’s communes” with the goal of rapidly industrializing agriculture and heavy industry.

The campaign failed catastrophically due to unrealistic production targets, lack of coordination, and economic mismanagement, resulting in widespread famine and millions of deaths. Mao later acknowledged the failure of the policy, openly admitting his limitations in economic planning:

“Coal and iron do not move by themselves. I focused only on revolution and understood nothing about industrial planning.”The Great Leap Forward was officially abandoned in 1961, marking one of the most severe economic disasters in modern history.

The Cultural Revolution and Total Ideological Control

In the mid-1960s, Mao Zedong initiated the Cultural Revolution, a radical movement aimed at eliminating perceived “bourgeois” elements from Chinese society. Universities were closed for nearly a decade, intellectuals were persecuted, and Mao’s writings became compulsory study material nationwide.

Youth groups known as the Red Guards enforced ideological conformity through mass campaigns, public humiliations, imprisonment, and violence. Urban spaces were saturated with propaganda posters bearing Mao’s image, and cultural heritage sites were systematically destroyed.

The Cultural Revolution caused immense social, cultural, and economic damage and resulted in millions of deaths. Although the movement gradually lost momentum in the early 1970s, its long-term consequences deeply scarred Chinese society.

Death, Succession, and Historical Assessment

Mao Zedong died on September 9, 1976. His death was concealed from the public for ten days. A prolonged power struggle followed, during which figures such as Zhou Enlai and later Deng Xiaoping shaped China’s post-Mao political direction.

Mao ruled as a highly authoritarian leader whose policies unified China under a communist system but at an enormous human cost. His legacy remains deeply contested, combining revolutionary transformation with widespread repression and suffering.

Personal Life and Inner Circle

Mao Zedong married Yang Kaihui, who was executed in 1927. He later married He Zizhen in 1931, divorcing in 1942. His final marriage was to actress Jiang Qing (born Lan Ping), a central figure during the Cultural Revolution and a member of the “Gang of Four.”

Global Ideological Influence

Mao Zedong profoundly influenced communist and revolutionary movements worldwide. Maoism adapted Marxist theory to agrarian societies and inspired movements across Asia, Africa, and Latin America, leaving a lasting imprint on global political thought.

Source: Biyografiler.com

Frequently asked questions about Mao Zedong

Who is Mao Zedong?, Mao Zedong biography, Mao Zedong life story, Mao Zedong age, Mao Zedong facts, Mao Zedong birthplace, Mao Zedong photos, Mao Zedong videos, Mao Zedong career

Related Biographies

Nicolas Maduro

Head of State, Politician

Delcy Rodriguez

Politician, Lawyer, Diplomat

Marco Rubio

Politician, Diplomat

Gustavo Petro

Politician, Economist, President

Ali Khamenei

Religious Leader, Politician

Reza Pahlavi

Military Officer, Monarch

Maria Corina Machado

Politician, Political Activist

Bob Dylan

Singer, Songwriter, Musician, Author

Prince Rogers Nelson

Singer, Songwriter, Musician

Kurt Cobain

Singer, Songwriter, Musician

Didier Drogba

Professional footballer

Iker Casillas

Professional footballer

Delcy Rodriguez

Politician, Lawyer, Diplomat

Giorgia Meloni

Politician, Journalist

Miguel Diaz-Canel

Politician

Natascha McElhone

Actress, Author

Ali Khamenei

Religious Leader, Politician

Ben Affleck

Actor, Film Director, Screenwriter