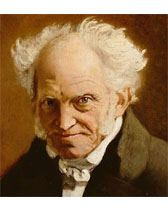

Arthur Schopenhauer

The Philosopher of Pessimism

Born on February 22, 1788

Died on September 21, 1860

Age at death: 72

Profession: Philosopher

Place of Birth: Danzig, Poland

Place of Death: Frankfurt, Germany

Arthur Schopenhauer was among the earliest and most original figures in German philosophy to mount a sustained opposition to the rational optimism of Enlightenment thought. Rejecting the belief that reason, moral progress, or historical purpose governs the world, he argued instead that existence is driven by blind, irrational forces. Seeing life itself as inseparable from suffering, Arthur Schopenhauer developed a philosophy of pessimism shaped by emotional isolation, intellectual independence, and a lifelong sense of alienation from society.

Early Life and Family Background

Arthur Schopenhauer was born on February 22, 1788, in Danzig into a wealthy merchant family. His father, Heinrich Floris Schopenhauer, was a prosperous trader, while his mother, Johanna Schopenhauer, was socially ambitious and later became a successful novelist and salon hostess. In 1793, the family relocated to Hamburg, a major commercial city whose culture of trade and status would later become a target of Schopenhauer’s contempt for bourgeois ambition.

He grew up alongside his younger sister, Adele Schopenhauer, and received his early education at the Hamburger Rungesche Privatschule. The school’s strict discipline and classical learning contributed to his early intellectual seriousness, but it also sharpened a temperament that was already inclined toward independence, impatience with authority, and emotional withdrawal.

European Travels and Early Worldview

Rather than allowing his son to proceed directly into conventional academic training, Heinrich Floris Schopenhauer insisted that Arthur Schopenhauer undertake a broad educational journey across Europe. Between 1803 and 1804, he traveled through the Netherlands, France, Sweden, Switzerland, Silesia, Prussia, and England, gaining firsthand exposure to social hierarchies, national identities, and political institutions.

He spent significant time in Wimbledon to improve his English, an experience that reinforced his observational style: attentive to manners, class structures, and the distance between public virtue and private motive. These travels fostered a deep skepticism toward nationalism, social conventions, and human ambition, encouraging the belief that the grand narratives societies tell about themselves often conceal more basic psychological drives.

In later life, this early international perspective contributed to his hostility toward mass movements, ideological optimism, and sentimental moralizing. The world he saw appeared less like a rational order moving toward improvement and more like a theater of competing desires.

Commercial Training and Break with Bourgeois Life

At his father’s request, Arthur Schopenhauer entered commercial training in Danzig and later Hamburg. The discipline of commerce—calculating profit, cultivating connections, and submitting to business routines—conflicted with his intellectual inclinations and intensified his sense that ordinary social life is organized around vanity and acquisition.

Following his father’s sudden and unexplained death in April 1805, Schopenhauer abandoned commerce entirely. His mother moved to Weimar with Adele Schopenhauer, while he remained behind, emotionally estranged and increasingly determined to pursue an academic path on his own terms.

The rupture marked more than a career change. It became an early practical confirmation of a theme that would recur throughout his philosophy: that the dominant expectations of society rarely align with the inner reality of the individual, and that human life is structured by pressures that often feel impersonal and coercive.

University Education and Early Works

In 1809, Arthur Schopenhauer enrolled at the University of Göttingen to study medicine but soon turned decisively toward philosophy. His shift reflected a conviction that the central questions of existence were not technical problems of the body but metaphysical problems of meaning, suffering, and the limits of rational explanation.

He later continued his studies at the University of Berlin, where German Idealism was dominant and where he encountered philosophical systems he came to view as grandiose, politically convenient, and intellectually dishonest. Even as a student, he positioned himself against academic fashion and cultivated an identity as an outsider.

On October 18, 1813, he earned his doctorate from the University of Jena with his dissertation On the Fourfold Root of the Principle of Sufficient Reason. The work set out a systematic account of different forms of explanation and justification, signaling his commitment to rigor and conceptual clarity.

One of the earliest readers of this dissertation was Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, with whom Schopenhauer later exchanged ideas on aesthetics and the philosophy of nature. The connection mattered not only intellectually but symbolically: it located Schopenhauer within a wider cultural world beyond university philosophy, even as he continued to reject academic orthodoxy.

Dresden Years and Eastern Influence

In 1814, Arthur Schopenhauer settled temporarily in Dresden, where access to rich library collections supported an intense period of reading and composition. This environment helped him consolidate a worldview increasingly centered on the problem of suffering and the psychological mechanics of desire.

During these years, he became deeply influenced by Eastern philosophy, particularly Hinduism and Buddhism. His study of the Upanishads and Buddhist texts offered a framework in which desire is not celebrated as self-fulfillment but diagnosed as bondage—an interpretation that aligned closely with his own pessimistic conclusions.

He also developed sharp positions in the philosophy of nature. He criticized the mechanistic worldview associated with Isaac Newton while praising Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s intuitive approach, which he regarded as closer to lived experience and less trapped in abstraction.

The result was a distinctive intellectual synthesis: Kantian limits on knowledge, Platonic metaphysical structure, and Eastern ethical seriousness, all organized around the thesis that the deepest engine of life is not reason but impulse.

Personal Conflicts and Chosen Solitude

Arthur Schopenhauer’s personal relationships were turbulent and often painful, and he repeatedly treated biography as evidence for metaphysics. His early involvement with Karoline Jagemann contributed to emotional crises that reinforced his belief that erotic desire enslaves human beings to suffering rather than delivering lasting happiness.

His relationship with Johanna Schopenhauer deteriorated as she openly mocked his philosophical ambitions, despite presiding over salons attended by major cultural figures, including Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. To Schopenhauer, the contrast between salon culture’s sociability and his own inward seriousness became proof that intellectual life could be distorted into performance and status-seeking.

Eventually, he severed ties with his mother completely and chose a life of intellectual solitude. This withdrawal was not only personal retreat but also a lived expression of his distrust of social life, which he increasingly saw as organized around rivalry, illusion, and cruelty disguised as civility.

The World as Will and Representation

In 1819, Arthur Schopenhauer traveled through Italy, visiting Venice, Rome, Naples, Milan, and Paestum. The journey sharpened his interest in art and aesthetics, which would become central to his belief that aesthetic contemplation offers a rare, temporary release from the pressures of desire.

That same year, he published his principal work, The World as Will and Representation. In it, he argued that the world as humans experience it is “representation,” structured by the mind’s forms of perception and understanding, while the underlying essence of reality is an irrational “will” that strives endlessly without final purpose.

Reason and consciousness, in this view, do not govern existence; they serve the will’s ceaseless demands. This is why suffering is not an accident of life but a structural feature of it: striving produces need, satisfaction fades, and new longing takes its place.

Yet Schopenhauer’s system also contained forms of relief. He emphasized art as a temporary suspension of the will and defended compassion and ascetic self-denial as the most serious ethical responses to a world defined by craving and pain.

Berlin Lectures and Conflict with Hegel

In 1820, Arthur Schopenhauer was appointed lecturer at the University of Berlin. Convinced that academic philosophy rewarded obscurity and political convenience rather than truth, he staged a direct confrontation with the era’s dominant figure by scheduling his lectures at the same hour as those of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel.

Schopenhauer regarded Hegel as the embodiment of philosophical fraud and dismissed his system as empty abstraction designed to flatter authority. The gamble failed: students overwhelmingly favored Hegel, and Schopenhauer’s lectures attracted almost no audience.

The episode hardened his hostility toward universities and confirmed his self-image as an intellectual outsider. He abandoned academic ambitions and committed himself to writing outside institutional structures, preferring obscurity to compromise.

Frankfurt Years and Late Recognition

During the cholera epidemic of 1831, Arthur Schopenhauer fled Berlin and settled permanently in Frankfurt. There he lived a reclusive life devoted to writing, reflection, and long walks, often accompanied by his dog, and he cultivated routines that reflected his preference for solitude and controlled habits.

His private life continued to mirror the disappointments that fueled his philosophy. His romantic relationship with Caroline Richter Medon ended decisively when she refused to abandon her child for him, reinforcing his belief that attachments demand sacrifices many people will not make—and that love often intensifies suffering rather than easing it.

For years, his work received little attention, and he watched other philosophical systems dominate German intellectual life. Then recognition arrived late: in 1853, the publication of Parerga and Paralipomena brought him international fame, transforming him into a celebrated critic of academic orthodoxy and a philosophical iconoclast.

Influence and Philosophical Legacy

Arthur Schopenhauer built upon Immanuel Kant’s distinction between appearance and thing-in-itself while rejecting the moral optimism that many readers drew from modern philosophy. He admired Plato’s theory of Ideas and incorporated elements of Buddhist compassion and ascetic discipline into his ethics, producing a system that treated suffering as central rather than incidental to human life.

His influence spread far beyond professional philosophy. Richard Wagner drew on Schopenhauer’s metaphysics and his elevation of music as a privileged art form, while Friedrich Nietzsche initially regarded Arthur Schopenhauer as his first and greatest intellectual mentor before later breaking away.

Writers such as Leo Tolstoy and later existential thinkers found in Schopenhauer a ruthless clarity about the instability of happiness and the psychology of desire. Over time, his thought also proved important for modern discussions of pessimism, the limits of rational self-mastery, and the role of aesthetic experience as refuge.

Death

Arthur Schopenhauer died on September 21, 1860, in Frankfurt, Germany, at the age of 72. His reputation continued to grow after his death, and he came to be widely regarded as the most influential pessimist in Western philosophy, reshaping debates in metaphysics, ethics, psychology, and aesthetics by insisting that suffering—not reason—lies at the core of human existence.

Major Works

On the Fourfold Root of the Principle of Sufficient Reason (1813)

The World as Will and Representation (1818–1819)

On the Will in Nature (1836)

On the Freedom of the Human Will (1839)

The Two Fundamental Problems of Ethics (1841)

Parerga and Paralipomena (1851)

Selected Quotations

Source: Biyografiler.com

Frequently asked questions about Arthur Schopenhauer

Who is Arthur Schopenhauer?, Arthur Schopenhauer biography, Arthur Schopenhauer life story, Arthur Schopenhauer age, Arthur Schopenhauer facts, Arthur Schopenhauer birthplace, Arthur Schopenhauer photos, Arthur Schopenhauer videos, Arthur Schopenhauer career

Related Biographies

Catherine O'Hara

Actress

Elena Andreyevna Rybakina

Professional Tennis Player

Giorgia Meloni

Politician, Journalist

Ali Khamenei

Religious Leader, Politician

Sam Altman

Entrepreneur, Investor, CEO

Jacob Elordi

Actor, Model

Ilya Sutskever

Computer Scientist, Researcher

Josh Hawley

Politician, Lawyer

Kevin Warsh

Economist

Hina Khan

Actress

Gwyneth Paltrow

Actress

Danny Glover

Actor, Political Activist

Bad Bunny

Rapper, Songwriter

Alain Delon

Actor, Director, Producer, Screenwriter

Antonio Banderas

Actor

Jeffrey Epstein

Businessperson

Demi Moore

Actress

Giorgia Meloni

Politician, Journalist