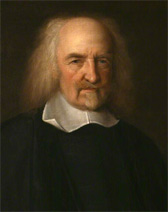

Thomas Hobbes

The Philosopher of Absolute Sovereignty

Born on April 5, 1588

Died on December 4, 1679

Age at death: 91

Profession: Philosopher, Political Theorist

Place of Birth: Westport (present-day Wiltshire), England

Place of Death: Derbyshire, England

Thomas Hobbes was one of the central figures in the political thought system upon which the British Empire was later grounded. His most famous work, Leviathan, published in 1651, articulated the idea that fundamental human instincts are inherently selfish.

Thomas Hobbes was born on April 5, 1588, in Westport, England, an area now known as Wiltshire. His father, also named Thomas, served as the parish priest of Charlton and Westport. Following a public altercation with another clergyman in front of his own church, Hobbes’s father was reassigned to London, leaving Thomas and his three siblings in the care of his elder brother, Francis. Hobbes began his education at the Westport church, continued at Malmesbury School, and later attended a private school. Due to his academic promise, he entered Magdalen Hall, affiliated with Hertford College, Oxford, in 1603. The headmaster, John Wilkinson, was a Puritan, and Hobbes was deeply influenced by his views.

Thomas Hobbes was not only a major thinker in English history but also one of the pioneers of a transformative shift in global political philosophy. Living in a period marked by severe political crises and civil war, Hobbes developed ideas that would profoundly alter human thought. His work inspired later secular thinkers such as Baruch Spinoza and played a crucial role in the emergence of modern democratic theory.

During his university years, Hobbes pursued an independent course of study, as he had little faith in formal education. While studying, he began tutoring William, the son of William Cavendish, the Baron of Hardwick. The two formed a close friendship and embarked on a Grand Tour together in 1610. Hobbes introduced William to European scientific and critical methods that stood in sharp contrast to the philosophy taught at Oxford.

Although he admired thinkers such as Ben Jonson and Francis Bacon, Hobbes made little effort to engage seriously with philosophy until 1629. After the death of his employer, the Earl of Devonshire, his widow terminated his position. Soon after, Sir Gervase Clifton offered him work as a tutor. By 1631, Hobbes had returned to the Cavendish household, this time teaching the son of his former student William. Over the next seven years, he deepened his knowledge of the major philosophical debates that increasingly fascinated him.

In 1636, Hobbes visited Florence and later took part in regular philosophical discussions in Paris organized by Marin Mersenne. From 1637 onward, he began to see himself fully as a philosopher and scientist.

Thomas Hobbes initially focused on motion and momentum in physics, though he largely ignored experimental methods. Instead, he sought to integrate his philosophical system with physical principles. He began developing a systematic doctrine of bodies, aiming to explain physical phenomena universally in terms of motion and mechanical action.

He later described himself as feeling excluded from the “kingdom of nature and plants,” focusing instead on humanity. In one thesis, he explained how specific bodily motions generate uniquely human phenomena such as emotion, knowledge, passion, and intimacy. In another, he analyzed how men enter society and how their behavior must be regulated to prevent cruelty and misery.

Hobbes attempted to unite the distinct realms of “body,” “man,” and “state” into a single philosophical framework. In 1637, he returned to England, where disruptions to his philosophical plans caused him considerable frustration.

After the dissolution of the Short Parliament in 1640, he wrote a brief treatise titled The Elements of Law, Natural and Politic, which circulated privately in manuscript form and was later published without authorization. During the Long Parliament in November 1640, Hobbes realized the political impact of his ideas and soon moved to Paris, where he remained for the next eleven years, reuniting with his friend Mersenne.

Hobbes wrote a critique of Meditations on First Philosophy by René Descartes, which was published in 1641 along with Descartes’s replies. He completed the third part of De Cive in the same year; though initially circulated among a small group, it soon gained wide acclaim. Many of its arguments would later reappear in Leviathan. Apart from a short work on optics included in the 1644 collection Cogitata Physico-mathematica, Hobbes published little during this period, yet he remained highly respected in philosophical circles.

From the age of twenty, Hobbes had served as a tutor to the influential Cavendish family, gaining access to private libraries, travel opportunities, and powerful social networks. During this time, he learned Italian and German and resolved to devote his life to scientific inquiry.

His intellectual productivity was slow at first. His earliest major work, a translation of Thucydides’s History of the Peloponnesian War, was not completed until 1629. Hobbes undertook this translation during a period of civil conflict, believing that knowledge of the past was essential for determining right action in the present.

According to Hobbes himself, the most important intellectual moment of his life occurred when he was forty. While waiting for a friend, he entered a library and discovered a copy of Euclid’s geometry. This encounter sparked his lasting interest in mathematics, later reflected in his work A Short Tract on First Principles.

Throughout his long life, Hobbes produced numerous works. In France, he met thinkers such as René Descartes and Pierre Gassendi. Despite being born in the Elizabethan era, he outlived most major thinkers of the seventeenth century. At the age of ninety, he still participated in debates at the Royal Society.

Deeply influenced by new scientific hypotheses circulating in Europe, Hobbes rejected the idea that nature operated through inherent purposes. Instead, he argued that all phenomena could be explained through principles of motion, in line with emerging mechanical sciences. During his third European journey in 1636, he met Galileo Galilei, an encounter that further reinforced his commitment to mechanical philosophy.

The outbreak of the English Civil War between 1642 and 1644 led many royalists to flee to Europe, particularly Paris, where Hobbes found himself among familiar company. During this time, he resumed work on political theory. De Cive was republished in 1646 with a new preface, distributed widely through the Elsevier press in Amsterdam.

In 1647, Hobbes became a mathematics tutor to the Prince of Wales, the future Charles II, though their lessons ended in 1648 when the prince relocated to the Netherlands. Encouraged by royalist exiles, Hobbes began composing a comprehensive political treatise addressing the crisis of civil war, criticizing traditional religious doctrines and emphasizing rational solutions to contemporary problems.

While writing Leviathan, Hobbes remained mostly in or near Paris. After suffering a severe illness in 1647 that confined him for six months, he recovered and completed the work by 1650. In mid-1651, his masterpiece was published in full as Leviathan: or the Matter, Form, and Power of a Commonwealth, Ecclesiastical and Civil, immediately provoking both admiration and fierce criticism.

Despite subsequent publications such as The Elements of Law, Leviathan overshadowed all his other works. Its influence far exceeded anything Hobbes had anticipated. Though the book defended a reformed monarchy as a means of preventing civil war, it did not support the doctrine of the divine right of kings and openly criticized both Presbyterian and Catholic interpretations of scripture.

Thomas Hobbes was a rationalist in an age increasingly dominated by empirical science. He developed powerful metaphysical arguments in favor of a mechanistic worldview. Central to his political philosophy was his critical engagement with religion, culminating in Leviathan, where he explored the political implications of religious belief with unmatched depth.

Though Hobbes did not rely on experimental evidence, his elegant reasoning provided a strong theoretical foundation for later thinkers. He left behind a legacy soon taken up by John Locke and significantly influenced philosophers such as Baruch Spinoza.

Thomas Hobbes died at the age of ninety-one on December 4, 1679, in Derbyshire, England, after suffering from a severe bladder illness and paralysis. According to Hobbes, the universe consists solely of matter; philosophy concerns bodies formed from matter, which can only be studied through observation and experience. Concepts such as God, angels, spirits, and souls belong not to philosophy, but to theology.

Source: Biyografiler.com

Frequently asked questions about Thomas Hobbes

Who is Thomas Hobbes?, Thomas Hobbes biography, Thomas Hobbes life story, Thomas Hobbes age, Thomas Hobbes facts, Thomas Hobbes birthplace, Thomas Hobbes photos, Thomas Hobbes videos, Thomas Hobbes career

Related Biographies

Bad Bunny

Rapper, Songwriter

Giorgia Meloni

Politician, Journalist

Jacob Elordi

Actor, Model

Jeffrey Epstein

Businessperson

Sam Altman

Entrepreneur, Investor, CEO

Julio Iglesias

Singer, Songwriter

Pierre de Coubertin

Historian

David Yates

Film Director, Film Producer

Neil Simon

Screenwriter

Woody Harrelson

Actor

Ayumu Hirano

Snowboarder

D. H. Lawrence

Novelist, Poet

Eileen Gu

Freestyle Skier, Model

Jutta Leerdam

Speed Skater

Donald Trump Jr.

Business Leader

Jacob Elordi

Actor, Model

Bad Bunny

Rapper, Songwriter

Sam Altman

Entrepreneur, Investor, CEO