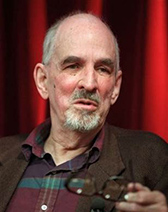

Ingmar Bergman

The Master of Existential Cinema

Born on July 14, 1918

Died on July 30, 2007

Age at death: 89

Profession: Film Director, Screenwriter

Place of Birth: Uppsala, Sweden

Place of Death: Fårö, Sweden

Ingmar Bergman was described by *Time* magazine in 2005 as “the greatest living film director in the world.” Born on July 14, 1918, in Uppsala, Sweden, as the son of a Protestant pastor, Bergman was raised under strict religious discipline. This rigid upbringing would later become one of the core psychological and thematic foundations of his cinema.

After receiving a severe religious education, Bergman began his career as a playwright and screenwriter. In his early twenties, he joined the Swedish State Theatres, quickly establishing himself both in theatre and cinema as a director. Raised in a deeply religious household, Bergman developed an opposing identity that led him toward intense existential inquiry. Over time, this inner conflict shaped the very skeleton of many of his films, most notably his masterpiece The Seventh Seal.

Bergman engraved his name into cinema history with metaphysical works such as The Seventh Seal, the profound psychological exploration of Persona, the family-centered epic Fanny and Alexander, and the intimate relational study Scenes from a Marriage. Beyond his storytelling, what truly distinguished Bergman’s films was their exceptional cinematography, marked by precision, intimacy, and emotional depth.

By the 1970s, Bergman had become a living legend across Europe. In 1976, following what he perceived as a humiliating interrogation by Swedish tax authorities regarding income declarations, he left Sweden in protest and relocated to Munich, Germany. A few years later, he returned to his homeland.

Bergman passed away on July 30, 2007, at the age of 89, on the island of Fårö in Sweden.

During his childhood, Bergman developed an affection toward his mother that bordered on romantic love. In his autobiographical work The Magic Lantern, he expressed this attachment as follows:

This Oedipal fixation undeniably surfaced in his films. Bergman consistently sided with women, elevating and foregrounding them, while male characters were often portrayed as emotionally dependent, childlike figures yearning for maternal affection—most clearly seen in Persona.

Similarly, in Wild Strawberries, Bergman depicted a professor who shares every moment of his journey with women—his assistant, daughter-in-law, lover, and companion—and finds comfort in this dynamic. Across his entire filmography, Bergman’s portrayal of women remains distinctly positive. In the same autobiographical context, he described his mother with striking emotional honesty:

Bergman never hesitated to criticize his pastor father or to openly confront his conflicting feelings of love and resentment toward his mother. He consistently demonstrated the courage to expose his inner world to audiences. He showed little interest in addressing social issues directly, instead favoring a deeply subjective cinematic approach.

His early years in cinema coincided with the aftermath of World War II—a time marked by despair, extreme religiosity, radical disbelief, rising suicide rates, and existential anxiety. These conditions deeply influenced Bergman’s psyche and, consequently, his films. In later years, his focus gradually shifted toward themes of love, separation, and human intimacy.

As Bergman matured, his cinematic language evolved. Close-up shots became dominant, narratives fragmented, and chronological constraints dissolved. This liberated structure allowed him to interrupt stories at will, reuse imagery, and create associative meaning. Viewers were no longer passive spectators but active participants, assembling the fragmented puzzle of his films themselves.

Ingmar Bergman remains one of cinema’s most fearless and influential auteurs—an artist who transformed personal trauma, spiritual doubt, and emotional vulnerability into timeless cinematic masterpieces.

Source: Biyografiler.com

Frequently asked questions about Ingmar Bergman

Who is Ingmar Bergman?, Ingmar Bergman biography, Ingmar Bergman life story, Ingmar Bergman age, Ingmar Bergman facts, Ingmar Bergman birthplace, Ingmar Bergman photos, Ingmar Bergman videos, Ingmar Bergman career

Bad Bunny

Rapper, Songwriter

Giorgia Meloni

Politician, Journalist

Jacob Elordi

Actor, Model

Julio Iglesias

Singer, Songwriter

Jeffrey Epstein

Businessperson

Sam Altman

Entrepreneur, Investor, CEO

Neil Simon

Screenwriter

Woody Harrelson

Actor

Ayumu Hirano

Snowboarder

D. H. Lawrence

Novelist, Poet

Erin Jackson

Speed Skater

Jutta Leerdam

Speed Skater

Eileen Gu

Freestyle Skier, Model

Donald Trump Jr.

Business Leader

Jacob Elordi

Actor, Model

Jutta Leerdam

Speed Skater

Mikaela Shiffrin

Alpine Ski Racer

Rishi Sunak

Politician